Today, in New Zealand's internet news site, Stuff, plus print features in various newspapers:

Maori are the inheritors of an impressive maritime

tradition. Their remote ancestors were

skilled sailors who burst into the western Pacific from southeast Asia over 3,000

years ago, to settle the islands of Fiji.

About a thousand years before Christ, they colonized Tonga and Samoa,

where Polynesian language and culture developed. From there, men and women sailed out from

this ancestral cradle, fanning out across the broad Pacific, and exploring more

of the earth’s surface than anyone ever before.

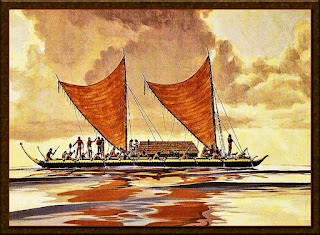

This amazing feat was made possible by their

evolution of the double-hulled canoe into a stable voyaging vessel, capable of

freighting plants, animals, provisions, as well as people. The big, graceful craft ranged as far east as

Rapanui (Easter Island), and probably made a landfall in South America, either

introducing the kumara, or carrying kumara sprouts back.

At a time when sailors in the Mediterranean were

experimenting with the fore-and-aft sail, Polynesian canoes powered by lateens

made the tough 4000 km voyage from the Tahitian archipelago to Hawaii, and then

back again, battling cross-currents, the doldrums, and contrary trade winds. And two hundred years before the era of

Columbus, Magellan, and Drake, Polynesians crossed 2000 miles of storm-tossed

ocean to the mountainous, deeply embayed islands of Aotearoa-New Zealand.

Their navigational science was astounding. Not

only were they familiar with the patterns of currents, clouds and swells, and

the migrations of birds, fish and whales, but they had a truly impressive

knowledge of star bearings. Great

directional stars and constellations—Matariki

(the Pleiades), Whetū-kura (Aldebaran),

Rehua (Antares), and Te matau o Maui (the

hook of Scorpio)—were as familiar to Polynesian navigators and priests as the

faces of their kin. Centuries before the

crew on Coumbus’s ship shivered at the prospect of falling off the edge of the

world, Polynesians knew perfectly well that the earth is round.

The

ancestors were also adept at the science of acclimatisation. It was an

intrinsic part of their successful settlement of the Pacific, and involved

plants and animals from as far away as New Guinea. This was because the islands they found,

though fertile, were barren. In Tahiti, for instance, there were only

two edible plants — a kind of borage, and coconut. Undeterred, they introduced

taro, kava, breadfruit, paper mulberry for tapa, pigs, chickens, dogs, bananas.

It is almost impossible to imagine what today’s tropical paradises would have

looked like without Polynesian horticultural brilliance.

They

applied the same system to Aotearoa-New Zealand. But this land was colder, heavily forested, the

soil not as fertile. Some of the cargo

was lost right away. The pigs and

chickens either did not survive the voyage, or died soon after landing, and

bananas, breadfruit, and coconuts failed to thrive. There were still dogs and rats—though the

rats might have been stowaways, it was possible to eat them. Carefully nurtured sprouts of taro, yams,

gourds, kumara, and paper mulberry acclimatized after a fashion, along with the

Pacific ti cabbage tree with its

sugary root. But the challenge was

enormous.

While the settlers were learned in the spheres of

astronomy, navigation, botany, zoology, medicine, and the social sciences, big gaps

in their knowledge were suddenly important.

They did not have chemistry, geology, physics, or metallurgy, for

instance. That those pioneers produced a flourishing society despite

these gaps is an achievement that should never be underrated.

No comments:

Post a Comment