Why do people act violently? What makes them do it? And what happens after the violent act?

I watched two thought-provoking films on Netflix, one a fictional drama, the other a documentary. Both were astounding, and the message was remarkably similar. What causes violence? How is it justified? And what happens after the violence has stopped?

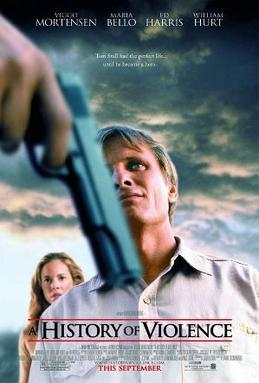

The drama was "A History of Violence."

I watched it despite the title, which sounded like the name of a documentary that would replicate rather too many historical episodes of violence ... Roman circuses, trench warfare, and so forth and so on. Nothing I wanted to see, promising nothing new. But I gave it a few minutes, and was immediately hooked into the most unusual and compelling theme. Violence.

It is the intriguing story of a man who reacts violently when his diner is being robbed, sending both thugs to a well deserved grave. So, was he a retired hero? From SAS or the Seals or something like that? That's what the media like to think, as they laud his actions in banner headlines and video clips.

No, he was no hero. Just a thug, another thug. A retired thug who has changed his name and become an ordinary, decent man, but still with a past as a hitman. And with the publicity his violent past catches up with him. There are nasty men out there who have been hankering after revenge for years, and now know where the lives.

The acting is amazing -- Viggo Mortensen, Ed Harris and William Hurt all threw their souls into this work, directed brilliantly by David Cronenberg. There is certainly violence, as the retired thug deals with the thugs who used to employ him, but the outcome is what is important. The past has caught up with his family life, too -- that decent, ordinary family, none of whom had the slightest idea of the monster who was living in their midst.

There is an interesting substory, of Mortensen's teenaged son, who is being bullied by a coven of teenaged thugs. He's an intelligent lad, and manages to talk them out of it when they want to pick an uneven fight, until the moment he snaps, and deals with them as his father would have dealt. Except that instead of sending them to the grave, he sends them to the emergency ward. He knew absolutely nothing of his father's past, so is a capacity for violence inherited?

Extremely well played by Ashton Holmes (a name to look out for), he is the first to deal with the emotional backlash that follows his own violence. When his father tries to tell him that what he did wasn't right, he storms off in a frenzy of emotion. The only way he can justify what he did to himself, perhaps, is that he did the right thing, and the bullies deserved what they got. But his father has told him that was wrong.

And it is his father's tragedy, too, that he is past the stage of self-justification for violence.

A superb film, one that I will watch again, just to mull over the messages.

The documentary has an equally unpromising title. It is called "Ordinary Men." But it turned out to be equally gripping and thought-provoking. And again, the theme was violence, and its effect on the perpetrators.

Presented by Christopher Browning, he American professor emeritus of history who authored the book with the same title on which the documentary is based, it is a study of the men in the Ordnungspolizei (Order Police) Reserve Unit 101, who rounded up Jews in Poland in 1941, slaughtering thousands, and sending thousands more to death camps.

And the title is right. They were very ordinary men. They weren't thugs. They weren't the victims of childhood violence. They didn't have a history of brutality. Some had university degrees. They were certainly not ardent Nazis. Yet they killed children. They ordered mothers to hold their babies to their breasts to save ammunition, as one shot would end the lives of both. They shot lines of helpless people at the lip of the pit where the bodies would fall. They did all this face-to-face. They talked to them as they led them into the forest to the pit. And yet they fired their guns and watched them collapse and die, over and over again.

So, what made them do it?

Had they been brain-washed? Those who had been to university had had professors who preached the Nazi ethic. Constant propaganda had assured them that Jews were Bolshevics, that they were "other" and not like them. Jews were the object of the offensive graffiti that smeared the walls in their home city, Hamburg.

And so, even though they were given the option of not taking part in the atrocities, very few of them stepped aside. One even took his bride along to watch as he "cleaned out" a ghetto, and she joined the team in the party afterwards.

A very interesting point that was made was that the killers were horribly affected after the first mass slaughtering. They vomited, and had nightmares. And because of this, some began to think of themselves as the victims. They felt sorry for themselves in this most grotesque way, and somehow, by twisted logic, it justified that they kept on with their killing.

But, for me, the most potent point was that Jews had been made into "others". They were different, too different for any "true" German to feel empathy for; it was like killing aliens, the enemy from some other sphere.

How general is this, historically? Does it explain atrocities like Kosovo, the Armenian massacres in Turkey, Rwanda, Cambodia? Is this why Australian aborigines were hunted down like bounty? Why English landlords could export grain for profit while Irish babies and children were starving to death? Because these people are "other"?

Watch both. It will horrify, but also make you think. Deeply.