Herodotus was more than a mere raconteur, for not only did he make an effort to get the facts right, but he wrote without preconceptions or bias. He called this collection of plain, unvarnished facts Historia, which in Greek means "inquiry," and so written history was born. And so he became the Father of History.

He wrote about ships and great voyages, too. Particularly interested in those sharp, adventurous, and energetic traders, the Phoenicians, he related amazing stories of their feats that he picked up during his tour of Egypt -- including an incredible circumnavigation of Africa.

Africa, except where it borders Asia (he wrote) is clearly surrounded by water. Necho, Pharaoh of Egypt, was the first we know of to demonstrate this. When he finished digging out the canal between the Nile and the Red Sea, he sent out a naval expedition manned by Phoenicians, instructing them to come home by way of the Straits of Gibraltar into the Mediterranean, and in that fashion get back to Egypt. So, setting out from the Red Sea, the Phoenicians sailed into the Indian Ocean. Each autumn they put in at whatever point of Africa they happened to be sailing by, sowed the soil, stayed there until harvest time, reaped the grain, and sailed on; so that two years went bay and it wasn't until the third that they doubled the Pillars of Hercules and made it back to Egypt. And they reported things which others can believe if they want but I cannot, to wit, that in sailing around Africa they had the sun on the right side.

(From Lionel Casson's wonderful account of the Ancient Mariners, where he substituted modern equivalents for the geographic names Herodotus used.)

So Herodotus clearly did not believe the story himself, and since his time many maritime historians have shared his doubts. Hundreds of arguments have been published -- and yet the voyage, as described, is feasible. The sun would indeed be always on the right. The problem of provisioning, which bedeviled thousands of exploration voyages, was easily solved by stopping on shore and growing food. And Herodotus has recently been proved right in another maritime matter, too.

During that tour of Egypt, he also became intrigued with some strange boats that plied the Nile. One, a cargo ship called a "baris" was described in detail, including a long account of its construction. This was something else that was hotly debated by maritime historians, as there was no other evidence of a baris whatsoever. But now, as The Guardian describes, Herodotus wasn't suffering from a rush of the imagination. The baris truly existed. And a wreck has been found.

“It wasn’t until we discovered this wreck that we realised Herodotus was right,” said Dr Damian Robinson, director of Oxford University’s centre for maritime archaeology, which is publishing the excavation’s findings. “What Herodotus described was what we were looking at.”

In 450 BC Herodotus witnessed the construction of a baris. He noted how the builders “cut planks two cubits long [around 100cm] and arrange them like bricks”. He added: “On the strong and long tenons [pieces of wood] they insert two-cubit planks. When they have built their ship in this way, they stretch beams over them… They obturate the seams from within with papyrus. There is one rudder, passing through a hole in the keel. The mast is of acacia and the sails of papyrus...”

Robinson said that previous scholars had “made some mistakes” in struggling to interpret the text without archaeological evidence. “It’s one of those enigmatic pieces. Scholars have argued exactly what it means for as long as we’ve been thinking of boats in this scholarly way,” he said.

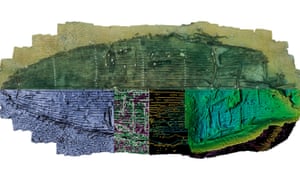

But the excavation of what has been called Ship 17 has revealed a vast crescent-shaped hull and a previously undocumented type of construction involving thick planks assembled with tenons – just as Herodotus observed, in describing a slightly smaller vessel.

Originally measuring up to 28 metres long, it is one of the first large-scale ancient Egyptian trading boats ever to have been discovered.

Robinson added: “Herodotus describes the boats as having long internal ribs. Nobody really knew what that meant… That structure’s never been seen archaeologically before. Then we discovered this form of construction on this particular boat and it absolutely is what Herodotus has been saying.”

About 70% of the hull has survived, well-preserved in the Nile silts. Acacia planks were held together with long tenon-ribs – some almost 2m long – and fastened with pegs, creating lines of ‘internal ribs’ within the hull. It was steered using an axial rudder with two circular openings for the steering oar and a step for a mast towards the centre of the vessel.

Robinson said: “Where planks are joined together to form the hull, they are usually joined by mortice and tenon joints which fasten one plank to the next. Here we have a completely unique form of construction, which is not seen anywhere else.”

Alexander Belov, whose book on the wreck, Ship 17: a Baris from Thonis-Heracleion, is published this month, suggests that the wreck’s nautical architecture is so close to Herodotus’s description, it could have been made in the very shipyard that he visited. Word-by-word analysis of his text demonstrates that almost every detail corresponds “exactly to the evidence”.

Ship 17 is the 17th of more than 70 vessels dating from the 8th to the 2nd century BC, discovered by Franck Goddio and a team – including Belov - from the European Institute for Underwater Archaeology during excavations in Aboukir bay, with which the Oxford Centre is involved.

No comments:

Post a Comment